New Year’s Day was one of the original five seasonal festivals in the Imperial Court in Kyoto, so you know this was a big day (where isn’t it a big day?)! The first three days of the New Year were sacred, so it was taboo to use a hearth to cook meals; save for ozōni (雑煮), a traditional soup made with rice cakes. Since women didn’t cook during the new year, Osechi-ryōri was usually made before the start of the first.

Back then (you know, before fast food and Uber Eats), osechi was only made up of vegetables boiled in soy sauce and sugar or mirin. As times changed along with food, so did the variety of Osechi-ryōri. Nowadays it basically means anything made for the New Year, be it fried foods, handmade foods, or takeaway foods. Those pressed for time can take the shortcut to specialty stores, grocery stores, or even convenience stores!

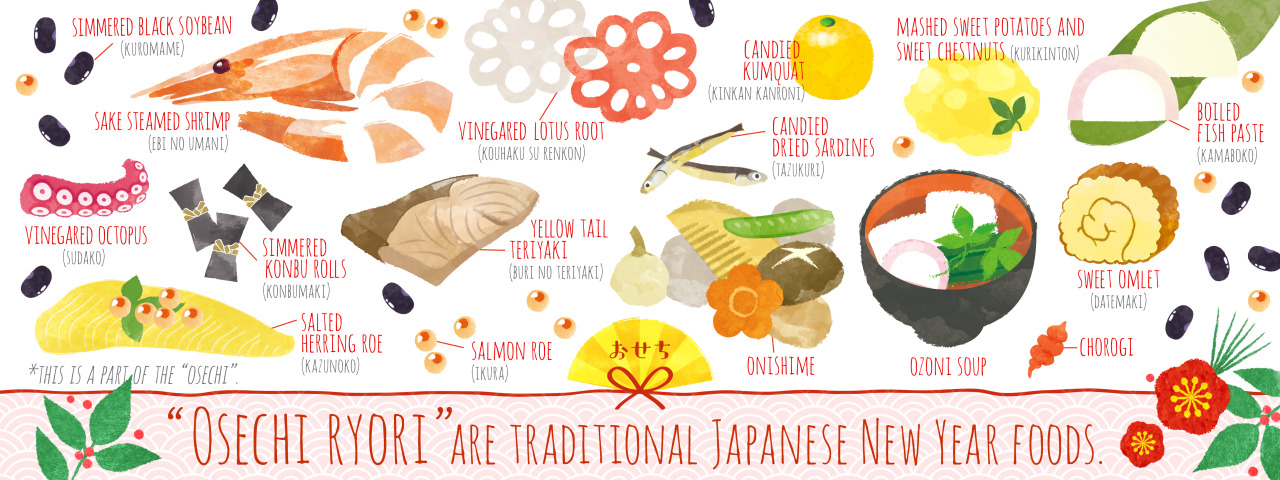

What’s in Osechi-ryōri?

This question will most likely vary from region to region, or even household to household in Japan, based on where you are. This list could go on and on, but know that every item has a special meaning according to the way it’s written in kanji. Think of these things as a pun, of sorts.

- Daidai (橙), a Japanese bitter orange, means “from generation to generation” when written as 代々. It stands for a wish for Children in the New Year.

- Datemaki (伊達巻) is a sweet, rolled omelette mixed with fish paste or shrimp. They represent a wish for auspicious days.

- Tazukuri (田作り), dried sardines cooked in soy sauce, goes back to when these fish were used to fertilize rice fields. The literal meaning is “rice paddy maker,” so they symbolize an abundant harvest.

- Kamaboko (蒲鉾), a broiled fish cake, is served in slices of red and white to represent the rising sun of Japan in a festive manner.

- Konbu (昆布) correlates with the word yorokobu, meaning “joy.”

- Kuro-mame (黒豆), black soybeans that stand for good health in the new year, as mame can also mean health.

- Tai (鯛), a fish called red sea-bream, is often associated with the word medetai, meaning congratulations. This symbolizes a lucky event.

- Nishiki tamago (錦卵/二色玉子), an egg separated before cooking, has its yellow symbolizing gold, and its white symbolizing silver. Together, they symbolize wealth and good fortune.

There are more, and meanings and foods will vary with each region, which is just more reason to visit each one and see what they mean!

The New Year

The Japanese New Year is one of deep importance. It’s filled with good food, but it’s also a time for loved ones to return to the homes where they were born, see their parents and grandparents, and take more calculated, spiritual steps to ringing in the new year. Whereas Western cultures tend to spend Christmas holidays with their families, and sometimes New Years with their friends in a more festive atmosphere; Japan feels like it calms down in a more introspective manner over the New Year’s Holidays.

Apart from visiting temples and eating traditional foods, nearly all Japanese people can be found writing handwritten postcards to family and friends around the world. They’ll spend hours upon hours handwriting names and addresses (or at least printing them out in a way that looks like they were handwritten!) as a gesture of remembrance for those in their lives. Children also line up to their elders to get otoshidama, little red envelopes filled with money.

Nowadays, with less time and more access to convenience, stores will often prepare Osechi-ryōri for families before the New Year. Expensive, high class establishments can make family meals for $500-$1,000 each, while the usual runs from $100-200. There are still plenty of families still handmaking these wonderfully thoughtful meals, packed into boxes similarly shaped to bentos.

Come to Japan and eat one of these meals; then stay for the magic of a Japanese New Year.

Add Comment